As I already mentioned my dad prepared us well for school. Before every lesson in his big study he would say in English, “I am your teacher.” He wanted to acquaint us with a foreign language early on in life. He refused to teach us Russian, which actually would have been more useful in a communist state controlled by the Soviet Union.

At this point I want to insert a story which I forgot to tell earlier.

When the Soviet troops first occupied Gotha, my mother was ordered to work for a commander who had taken over a neighbor’s house as residence. For a few hours every day my mother had to do housework for him in exchange for some precious victuals.

One day when my mother reported for work, the whole household of the commander was in disarray and upheaval. The commander had lost his precious ring. An extensive search by all the members of his household had been unsuccessful. The ring was not found. Finally, my mother was accused of having stolen the ring.

The commander told my mother that she had to return the ring by the next morning or there would be dire consequences.

My mother was scared to death. She had seen and admired the ring, but had no idea where it was.

She spent the night in agony not knowing what to do. Finally, after many prayers she decided to offer the commander all her jewellery the next day to prove her innocence,

The following morning, weak with fear and apprehension she arrived at her work place. She was immediately sent to the commander’s office who held out his hand to her when she entered. My mother could not believe her eyes, when she saw the precious ring sparkling on his finger.

In his broken German the commander explained that when he was getting dressed that morning he had felt a small object in the lining of his jacket. On further investigation it felt like his lost ring. He remembered suddenly that he had put it in the pocket of his jacket for some reason my mother could not understand. Maybe to keep it safe. His coat pocket had a small tear in the seam and the ring had slipped through it into the silk lining. That the ring was found in the nick of time to save my mother from dire consequences is another miracle.

From that day on the commander rewarded her more generously for her work.

After this digression I want to continue my stories of our early school experiences.

Math was always fun. My brother and I had competitions in mental math, which I would usually win. Until the last years in high school I always outperformed my brother. But then he surpassed me and I could never catch up. Calculus was my downfall.

We had to memorize poems, ballads and of course lots of folk songs, which we would sing on long hikes in the beautiful forests of Thuringia. Most of the songs are still fresh in my mind. They bring back happy memories of picking berries, swimming in rivers and lakes, and of picnics under beautiful tress. On these outings my dad would tell us legends and fairy tales often connected to the folklore of the region.

Since the German language has fairly consistent phonetic rules, I learned reading almost on my own, before I entered school.

The famous German “Zuckertüte” or sugar cone bag originated in Thuringia in a town close to Gotha. This very large, brightly decorated cone shaped paper bag was filled with chocolates, candies and other delicacies or little gifts to “sweeten” the first day of school. I wished we had a picture of ours. But at that time my parents did not have the means to buy films.

First Day of School

First Day of School

For the first few years we only had a few hours of school every morning including Saturdays. Students were expected to do homework and practice their new skills after school. Since my brother and I were fast learners, we had lots of free time to play when we returned home for lunch.

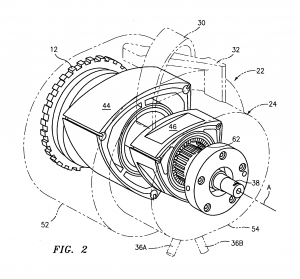

My brother had an inquisitive mind and constantly tried to find out how things worked or how they were made. I would often discover that my toys or dolls were broken or taken apart. They had fallen victim to my brother’s curiosity. It would upset me tremendously.

Although my parents expressed some sympathy to me, they never punished my brother or tried to change his behavior. They not only condoned his often destructive explorations, but almost encouraged them. They were proud of his clever findings and discoveries.

In the name of science I was expected to sacrifice my toys.

I do not have many memories of our early school days. But I remember that our teacher was called Frau Gans (Mrs. Goose). My dad was very much amused by her name. In German you say “dumme Gans” to a “”dumb female. Our teacher definitely was not ” a stupid goose.”

Both my brother and I were artistic and liked to draw and paint.

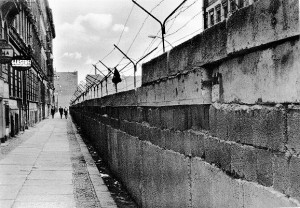

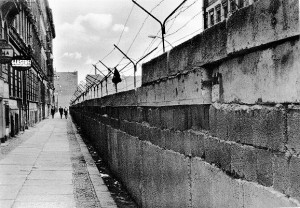

I produced my first “master piece” in grade one. We were supposed to paint a picture of a wall. Mrs. Goose was very much impressed with my work because i painted such a realistic looking brick wall and a happy worker beside it. My dad was a bit puzzled by this unusual theme. “Why paint an ugly wall?” he asked. Ten years later the Berlin Wall was built to permanently separate the two parts of Germany. Maybe this early art exercise in wall paintings was the first step to glorify wall building.

Scarlet Fever and Diphtheria

Shortly before we started school, my brother and I fell ill with scarlet fever, a very serious disease at that time often leading to death.

We were hospitalized. It was a very traumatic time for us. Missing my mother was almost more agonizing for me than the pain and the fever of this savage disease.

My brother was far worse off than I was and was put in an isolation chamber partitioned from the ward by glass walls.

I often saw doctors and nurses bend over him with serious expressions on their faces.

My mother knew how distressed we were. Many times during the day and even at night she would race on her bike to the hospital. Disregarding strict visitor regulations she would find ways to sneak into our ward and comfort us until she was asked to leave. Since my bed was close to a window, I would often stare out onto the street in the hope to spot my mother in the distance on her bike.

Antibiotics were very scarce in East Germany. Even in the West there was only a limited supply because of the recent war.

My brother was at the point of death when a desperate doctor asked my mother if she had relatives in West Germany. He suggested to phone them and ask for antibiotics to be sent to the hospital. He helped my mother to contact her aunt via his private phone and make arrangements with a doctor in the West. This was a precarious undertaking because contact with the West was considered a serious offense. Miraculously the mission was successful.

When the antibiotics finally arrived, I was already on the road to recovery. However, for my brother they came just in the nick of time. He was saved from death but suffered from a weakened heart for the rest of his life.

Shortly after we recovered, my newly wed sister and husband came down with a severe case of diphtheria, from which they took a long time to recover. They were in quarantine for many weeks and my parents had to look after their infant son during that time.

Looking back now I wonder how my parents coped with all these extreme hardships.

As my mother often told us, my brother and I were the reason why they never despaired or gave up. We were their pride and joy. Trying to raise us for a better future gave them strength and hope. Especially my mother was prepared to sacrifice anything for our well -being and prospects for a happy future. Without personal freedom these prospects were compromised. My parents felt increasingly oppressed by the totalitarian state.

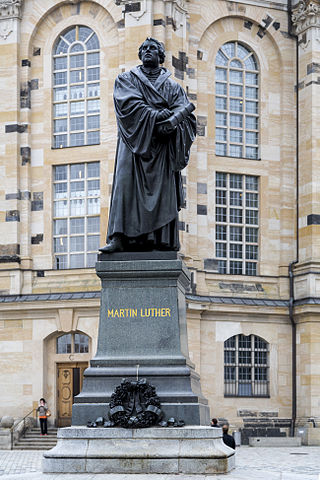

However, in this boring physical environment we had the most exciting experiences. We would vicariously relive mankind’s quest for scientific knowledge and spiritual truths. Most of our teachers were passionate about expanding our minds. They tried to teach us skills to foster critical thinking, problem solving and effective oral and written communication.

However, in this boring physical environment we had the most exciting experiences. We would vicariously relive mankind’s quest for scientific knowledge and spiritual truths. Most of our teachers were passionate about expanding our minds. They tried to teach us skills to foster critical thinking, problem solving and effective oral and written communication.